SUPERSTAR: THE KAREN CARPENTER STORY

Many of the themes that emerge in Haynes’ films (rock stardom in Velvet Goldmine, the Dylan-inspired I'm Not There, dark personal secrets in Far From Heaven and Poison, stultifying societal pressures in Safe) can be traced back to his film debut. Fifteen years ago Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story announced his presence on the American film scene with a bang, as the film caused a sensation and was quickly withdrawn from circulation due to a lawsuit from Karen's brother and musical partner, Richard Carpenter. It still lives on bootleg video and Haynes himself quietly showed a new print a few years back at a film festival in Spain. It’s unlikely that its legal status will change anytime soon (it is filled with film footage and pop recordings of the seventies that are presumably uncleared legally), which is a major loss for American film history. It is one of the great films of the eighties, overflowing with ideas about celebrity, consumer culture, feminine objectification and America’s loss of innocence.

Do people still remember The Carpenters, as their heyday drifts further and further back in our cultural consciousness? From 1970 to 1978 The Carpenters had twelve Top Ten singles, all light and airy confections portraying a calm new beginning that counterbalanced the turbulence of the late 1960s. This was pop music made by young people that your Lawrence Welk-loving grandparents could embrace. However, the soft commercial sheen concealed secrets, namely Richard’s homosexuality and Karen’s severe affliction with anorexia nervosa.

In 1983 Karen died of a heart attack in her mother’s home, a consequence of her illness. Haynes tells this story in a richly packed forty-three minutes, surprisingly emotionally involving for a film whose cast is manufactured by Mattel.

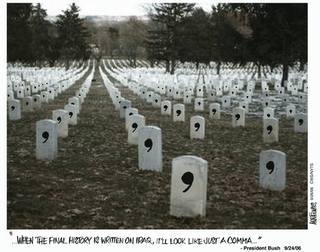

When people hear that Karen and Richard, as well as the rest of the cast, are played by dolls from the Barbie line, they tend to get the understandable impression that the piece is a spoofy satire, poking fun at the white bread image of lite-pop icons The Carpenters. This hardly the case. Sure, Karen's Barbie actress is employed for her 'perfect' underfed image, but after a few minutes you tune in to the vocal talents (especially Merrill Gruver and Michael Edwards as the musical duo and Melissa Brown as their controlling mother) and it becomes somewhat unnerving how much you can be moved, staring at a ten-inch piece of mass-produced plastic. As Karen signs her record contract, you see Holocaust footage of an emaciated corpse being thrown into a pit. As the Carpenters’ ubiquitous hits 'Close To You' and 'We've Only Just Begun' are played, you get facts, figures, and footage about the birth of the American supermarket, the bombing of Cambodia, and The Brady Bunch. Anorexia Nervosa is discussed in what appears to be a mock health education film. And as the syndrome’s side effect of a euphoric high is discussed, Karen is heard singing 'I'm On Top Of The World'. Within this context, all the American happy-faced cheer of the era comes crashing down as part of a cruel conspiracy to deny the truth about who we are and how we live. And Karen, the era’s angelic voice, becomes victim to its lies as well. 'I just want it to be perfect' she pines during a recording session. But perfection only lasts for a moment, if it exists at all.Last year, I showed this film to a film class I was teaching at an all-girl high school. Since the class was an hour and a half long, I took a number of short films to fill the time. However, after showing Superstar, a wide-ranging and spirited discussion consumed the remainder of the period. Our next class didn’t meet until three weeks later, yet the analysis instantly resumed. The girls discussed eating disorders, the media, and their relationships with their parents. Despite the film’s unusual tone and scattershot technique, it spoke to them directly and hit them hard. If Haynes had never made another film, Superstar alone would leave a large legacy.

SUPERSTAR: THE KAREN CARPENTER STORY will take some wiles on your part since it cannot legally be shown or sold, but like procuring Cuban cigars, you will impress yourself and others once you do. It is not terribly hard to find.